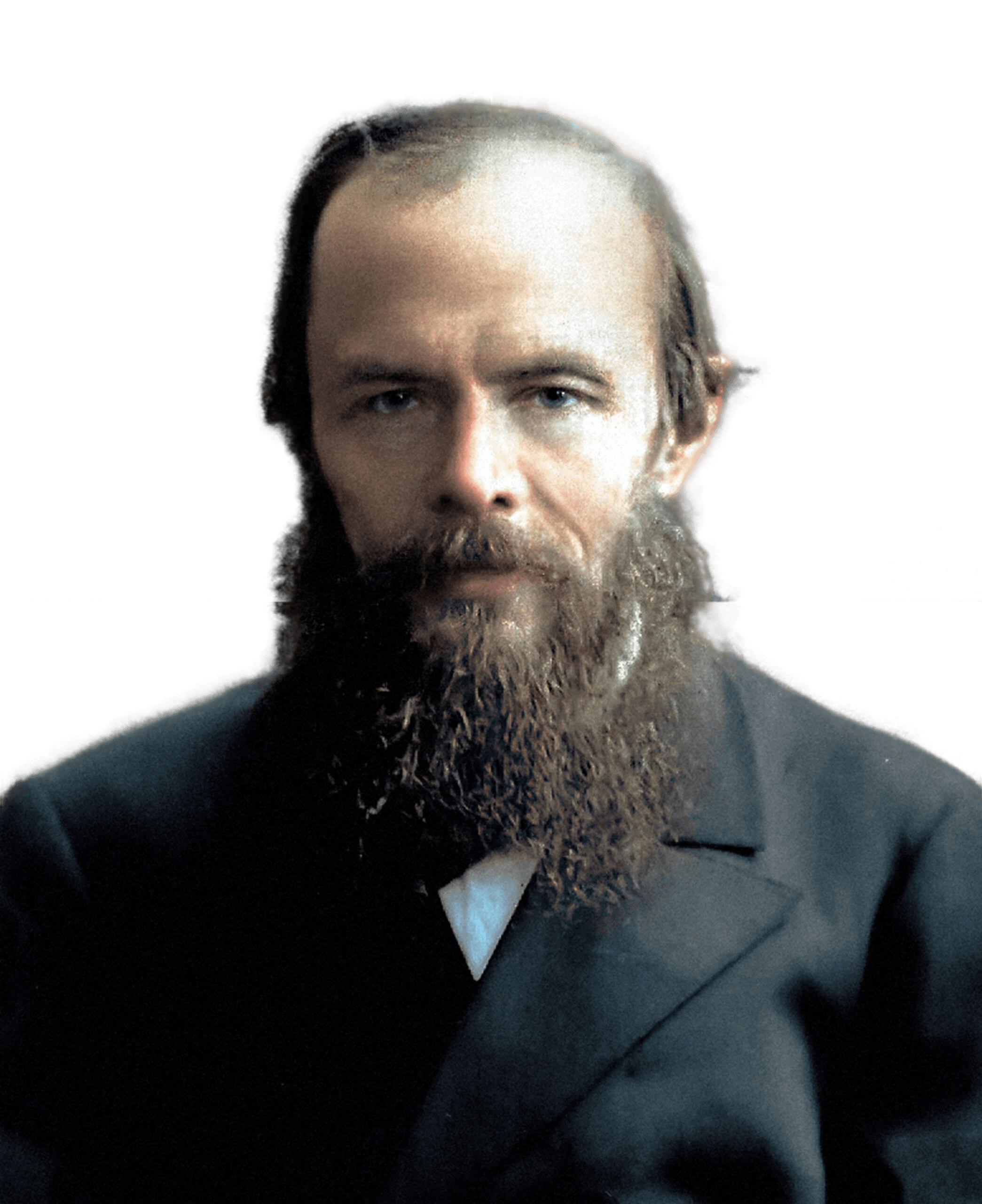

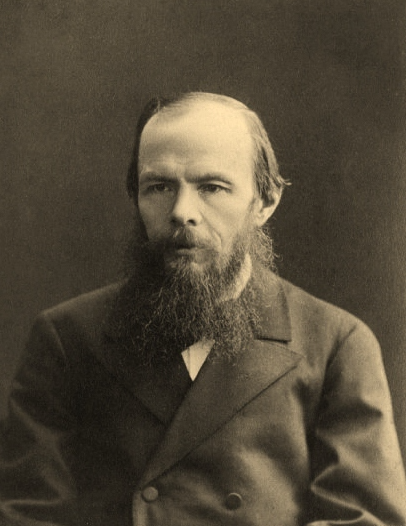

Fyodor Dostoevsky

Fyodor Dostoevsky dreamed of ёbecoming a writer from childhood. His first novel, Poor People, was praised by Nikolai Nekrasov and Vissarion Belinsky, and four of his later works were included in the “100 Best Books of All Times” list.

The Dostoevskys’ home life fostered imagination and curiosity. Later in his memoirs, the writer referred to his parents, eager to escape the commonplace and mediocrity, as ‘the best, the foremost people’. At family evenings in the living room they read aloud Karamzin, Derzhavin, Zhukovsky, Pushkin, Polevoy, Radcliffe. Later Fyodor Mikhailovich especially distinguished reading “History of the Russian State” by his father: “I was only ten years old when I already knew almost all major episodes of Russian history. Maria Fyodorovna taught the children to read. According to recollections, children were taught early, already at the age of four sat down at the book and said: “Learn! We started with cheap cheap popular fairy tales about Bova Korolevich and Yeruslan Lazarevich, tales about the Battle of Kulikovo, tales about Shut Balakirev and Ermak. The first serious book by which children were taught to read was One Hundred and Four Sacred Histories of the Old and New Testament. Half a century later, Dostoevsky managed to find an edition from his childhood, which he later “cherishes as a shrine”, saying that this book was “one of the first that struck me in life, I was still almost a baby then!

All his free time Dostoevsky read Homer, Corneille, Racine, Balzac, Hugo, Goethe, Hoffmann, Schiller, Shakespeare, Byron, among Russian authors – Derzhavin, Lermontov, Gogol, and almost all works of Pushkin knew by heart. According to the memoirs of Russian geographer Semenov-Tyan-Shansky, Dostoevsky was “more educated than many Russian writers of his time, such as Nekrasov, Panayev, Grigorovich, Pleshcheyev and even Gogol himself.

Inspired by what he had read, the young man took his own first steps in literary work at night. In the autumn of 1838 his fellow students at the Engineering School, influenced by Dostoevsky, organized a literary circle.

Political views

The writer was and remained a Russian man, inseparably linked to the people, but he did not deny the achievements of Western culture and civilisation. Dostoevsky’s views evolved over time: a former member of the Christian socialist utopian circle he became a religious conservative and during his third stay abroad he finally became a staunch monarchist.

Dostoevsky later called his political views of the Petrashevites ‘theoretical socialism’ in the spirit of Fourier’s system. After his first trip to Europe in 1862, “Dostoevsky becomes an opponent of the spread of universal, pan-European progressivism in Russia”, having spoken in his article “Winter Notes on Summer Impressions” (1863) of a sharp criticism of Western European bourgeois society, which substitutes freedom for “the million”. Dostoyevsky filled Herzen’s notion of “Russian socialism” with Christian content. Dostoevsky denied the division of society into classes and the class struggle, believing that atheistic socialism could not replace bourgeoisie as it was not fundamentally different from it. In the journals Vremya, Epoch and The Writer’s Diary, Dostoevsky gave free expression to opposing views.