20.12.2022

Although Dostoevsky denied the charges brought against him, the court found him “one of the most important criminals” for reading and “for failing to report the dissemination of a letter written by the writer Belinsky criminal about religion and the government”. Until November 13, 1849, the Military Court Commission sentenced Dostoyevsky to deprivation of all rights of estate and “death by firing squad”. On November 19 Dostoevsky’s death sentence was overturned by the Auditor General’s report “in view of the inadequacy of his guilt” with a sentence of eight years’ hard labour. At the end of November Emperor Nikolay I when confirming the sentence imposed on Dostoevsky by the Auditor-General’s office replaced his eight-year hard labour term by four years and his subsequent military service as a private soldier.

On December 22, 1849 in the Semyonovsky parade-ground the “death penalty by shooting” with the breaking of the sword over the head was read to the Petrashevites which was followed by the suspension of the execution and pardon. During the mock execution, the pardon and punishment of hard labour was announced at the last moment. One of those sentenced to execution, Nikolai Grigoriev, went insane. The feelings Dostoevsky may have felt before his execution are reflected in one of the monologues of Prince Myshkin in The Idiot. It is most likely that the writer’s political views began to change while still in the Petropavlovsky fortress, while his religious views were based on the worldview of orthodoxy. For instance, the petrashevik Lvov remembered Dostoyevsky’s words to Speshnev before the demonstration execution on the Semyonovsky Platz: “We shall be with Christ,” to which the latter replied, “A handful of ashes.” In 1849 Dostoevsky, implicated in the Petrashevsky case, was exiled to Siberia.

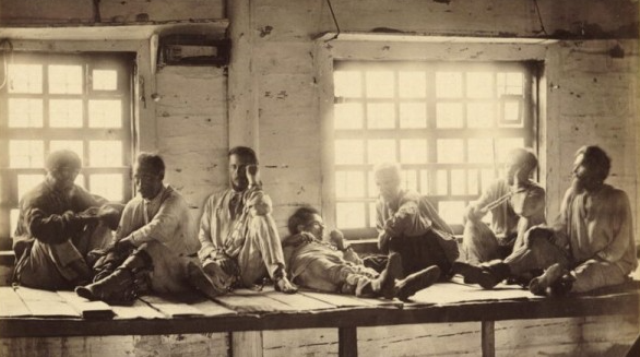

During a short stay in Tobolsk from 9 to 20 January 1850 on the way to the place of execution the wives of exiled Decembrists Muravyev, Annenkov and Fonvizin organised a meeting of the writer with other exiled petrashevites and through captain Smolkov handed each a Gospel with money (10 rubles) discreetly glued in the binding. Dostoevsky kept his copy of the Gospel his whole life as a relic. The next four years Dostoevsky spent in hard labour in Omsk. Apart from Dostoevsky, only one other 19th century Russian writer – Chernyshevsky – went through the hard school of hard labour. Prisoners were deprived of the right to correspond, but in the infirmary the writer was able to keep secret notes in the so-called “Siberian notebook” (“my notebook katornaya”). His impressions of his time in prison were reflected in his novel “Notes from the Dead House”. It took years for Dostoevsky to break the hostile estrangement towards himself as a nobleman, after which the prisoners began to accept him as one of their own. Miller, the writer’s first biographer, believed that hard labour was “a lesson in popular truth for Dostoevsky”. In 1850 the Polish magazine Biblioteka Warszawska had published excerpts from The Poor People and a positive review of the novel. The doctor Yermakov’s attached certificate to Dostoevsky’s resignation letter of 1858 addressed to Alexander II states that the writer’s time in prison was determined by his first medical statement about his illness: he had cerebral palsy.

After his release from prison Dostoevsky spent nearly a month in Omsk, where he became friends with Chokan Valikhanov, the future famous Kazakh traveller and ethnographer.

At the end of February 1854 Dostoevsky was sent as a private to the 7th Siberian linear battalion in Semipalatinsk. In the spring of that year he began an affair with Maria Dmitrievna Isayeva, who was married to a local official Alexander Ivanovich Isayev, a bitter drunkard. Some time later Isayev was transferred to Kuznetsk as a tavern keeper. On 14 August 1855 Fyodor Mikhailovich received a letter from Kuznetsk: Isayeva’s husband passed away after a long illness.

After the death of Emperor Nicholas I on February 18, 1855 Dostoevsky wrote a loyal poem dedicated to his widow, Empress Alexandra Feodorovna. Thanks to the petition of the commander of a separate Siberian corps, General of Infantry Gassfort, Dostoevsky was made a non-commissioned officer by order of the minister of war in connection with the manifesto of March 27, 1855 to mark the beginning of the reign of Alexander II and the granting of privileges and favors to a number of convicted criminals. Hoping for a pardon from the new Emperor Alexander II, Fyodor Mikhailovich wrote a letter to his old acquaintance, the hero of the defense of Sevastopol, Adjutant General Eduard Totleben, with a request to petition the Emperor. This letter was delivered to St Petersburg by the writer’s friend Baron Alexander Yegorovich Vrangel, who had published his memoirs after Dostoevsky’s death. Totleben obtained a definite pardon in a private audience with the Emperor. On the coronation day of Alexander II, August 26, 1856, a pardon was announced for the former Petrashevites. However, Alexander II ordered the writer to be secretly supervised until he was completely convinced of his trustworthiness. On October 20, 1856 Dostoevsky was made an ensign.

On 6 February 1857 Dostoevsky was married to Maria Isaeva in the Russian Orthodox Church in Kuznetsk. A week after the wedding the newlyweds travelled to Semipalatinsk and stayed four days in Barnaul with Semenov, where Dostoevsky had an epileptic seizure. Contrary to Dostoevsky’s expectations this marriage was not a happy one. Dostoevsky’s pardon (i.e. full amnesty and permission to publish) was declared by the highest decree on April 17, 1857, which returned the rights of the nobility to the Decembrists as well as to all Petrashevites. The period of imprisonment and military service was a turning point in Dostoevsky’s life: from being an undecided “seeker of truth in man” he turned into a deeply religious man whose only ideal for the rest of his life was Jesus Christ. All three of Dostoevsky’s “devotional” poems were never published during his lifetime. Dostoevsky’s first published work after his hard labour and exile was the short story ‘The Little Hero’, which took place after a full amnesty. In 1859 Dostoevsky’s novels Uncle’s Dream and The Village of Stepanchikovo and Its Inhabitants were published.