20.12.2022

On June 30, 1859 Dostoevsky was given a temporary ticket permitting him to leave for Tver, and on July 2 the writer left Semipalatinsk. At the end of December 1859 Dostoevsky returned to St. Petersburg with his wife and adopted son Pavel, but secret surveillance of the writer did not cease until the mid-1870s. Dostoevsky was released from police surveillance on 9 July 1875.

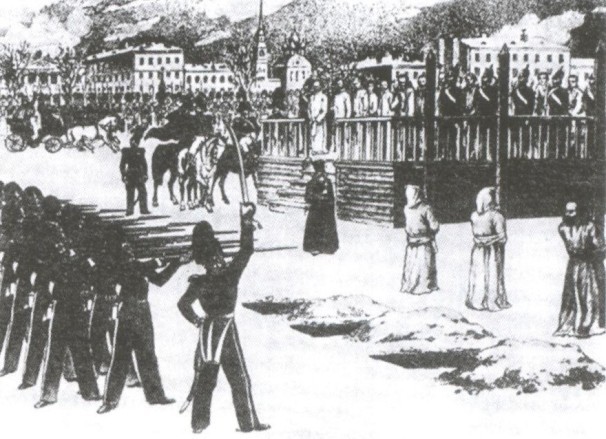

In 1860 a two-volume collection of Dostoevsky’s works was published. However, as his contemporaries failed to give credit to his novels Uncle’s Dream and The Village Stepanchikovo and Its Inhabitants, Dostoevsky needed a second high-profile literary debut, which was the publication of Notes from the Dead House. This pioneering work, whose genre is still imperfectly defined by literary critics, stunned Russian readers. For contemporaries, “Notes” was a revelation. No one had ever touched the subject of depicting the life of convicts before Dostoevsky. This work alone was enough for the writer to occupy his rightful place in Russian and world literature. According to Gertsen, Dostoevsky appeared in Notes from the Dead House as a Russian Dante who was descending into hell. Herzen compared Notes with Michelangelo’s fresco The Last Judgment and tried to translate the writer’s work into English, but because of the difficulty of translation the edition was not carried out.

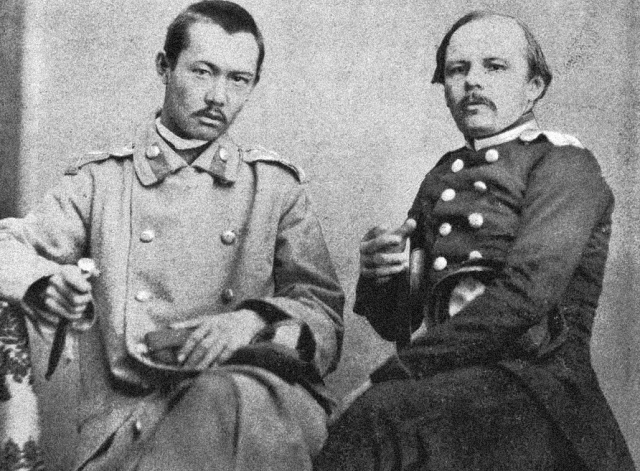

From early 1861, Fyodor Mikhailovich helped his brother Mikhail to publish his own literary and political magazine Vremya, after which, in 1863, the brothers began publishing the magazine Epokha. Such works by Dostoevsky as The Humiliated and the Insulted (1861), Notes from the Dead House, A Sketchy Anecdote (1862), Notes on Summer Impressions (1863) and Notes from Underground (1864) appeared on the pages of these magazines. Collaboration in the magazines Vremya and Epoch marked the beginning of Dostoevsky’s publicist activity, while his work with Strakhov and Grigoriev helped the Dostoevsky brothers to adopt the position of the Fatherland movement.

In the summer of 1862 Dostoevsky made his first trip abroad, visiting Germany, France, England, Switzerland, Italy and Austria. Although the main purpose of the trip was treatment at German spas, in Baden-Baden the writer became addicted to the ruinous game of roulette and was in constant need of money. Part of a second trip to Europe in the summer of 1863 Dostoevsky spent with a young emancipated woman, Apollinaria Suslova (“an infernal woman” according to the writer), whom he had also met in Wiesbaden in 1865. Dostoevsky’s love affair with Suslova, their complicated relationship and the writer’s attachment to roulette are reflected in his novel The Gambler. Dostoevsky visited casinos in Baden-Baden, Wiesbaden and Homburg in 1862, 1863, 1865, 1867, 1870 and 1871. He played roulette in Wiesbaden for the last time on 16 April 1871, when, after losing the roulette game, he gave up his passion for this game. Dostoevsky described his impressions of his first trip to Europe, his reflections on the ideals of the French Revolution – ‘Liberty, Equality and Fraternity’ – in a series of eight philosophical essays entitled ‘Winter Notes on Summer Impressions’. The writer “in his Paris and London impressions found inspiration and strength” to “declare himself an enemy of bourgeois progress”.

“Notes from the Underground”, which marked a new stage in the development of Dostoevsky’s talent, was to become parts of the great novel “Confession”, the unrealised idea of which originated in 1862. The first part of the hero’s philosophical confession “The Underground” was written in January and February and the second part (“A Tale of Wet Snow”) was written between March and May 1864. In the story, Dostoevsky acted as an innovator, endowing the reasoning of the “underground man” with great power of persuasiveness. Raskolnikov, Stavrogin and the Karamazov brothers inherited this “persuasiveness” in the monologues of subsequent novels of the “great five books”. Such an unusual device for contemporaries was the basis for the mistaken identification of the character with the author. Possessing his own notion of benefit the “underground paradoxalist”, who has “detached himself from the soil and the people’s principles”, leads a polemic not only with Chernyshevsky’s theory of “rational egoism”. His arguments are directed both against the rationalism and optimism of the 18th century Enlighteners (Rousseau and Diderot) and against supporters of the different camps of social and political struggle of the early 1860s. In 1864 the writer’s wife and elder brother passed away. During this period the socialist illusions of his youth (which were based on European socialist theories) are shattered, and the writer’s critical perception of bourgeois-liberal values is formed. Dostoevsky’s thoughts on this subject would later be reflected in the novels of the “Great Five Books” and The Writer’s Diary.