13.01.2023

Anna Grigoryevna Snitkina in her memoirs, rejecting jealousy, tried to objectively reproduce all her husband’s love interests.

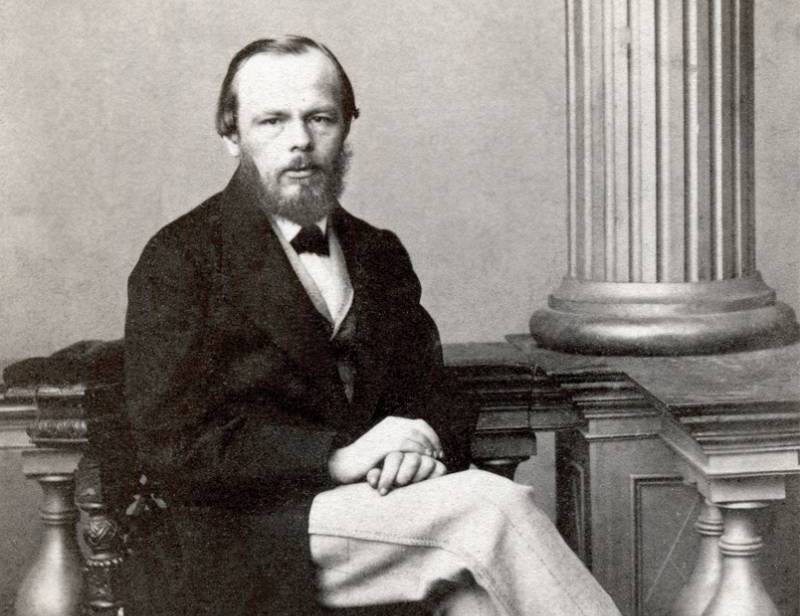

Noting that in his youth Dostoevsky “did not have a serious hot love for any woman” due to the fact that “he began to live a mental life too early,” and creativity, and then politics pushed personal life into the background, Anna Grigorievna still mentions the one who captivated the young writer.

Avdotya Panaeva, beautiful, intelligent, the idol of many young writers of the forties of the XIX century, conquered the young Dostoevsky. In letters to his brother Mikhail, to whom he confided all his secrets, the writer confessed: “Yesterday I visited Panayev for the first time and, it seems, fell in love with his wife. She is smart and pretty, in addition, amiable and straightforward to the last degree”, “I was seriously in love with Panaeva, now it’s passing, but I don’t know yet…” A. G. Dostoevskaya generously called it a fleeting infatuation and found the following, quite plausible excuse: Panaeva showed compassion for Fyodor Mikhailovich, who was subjected to ridicule by writers, and “met with heartfelt gratitude and tenderness of sincere infatuation on his part”.

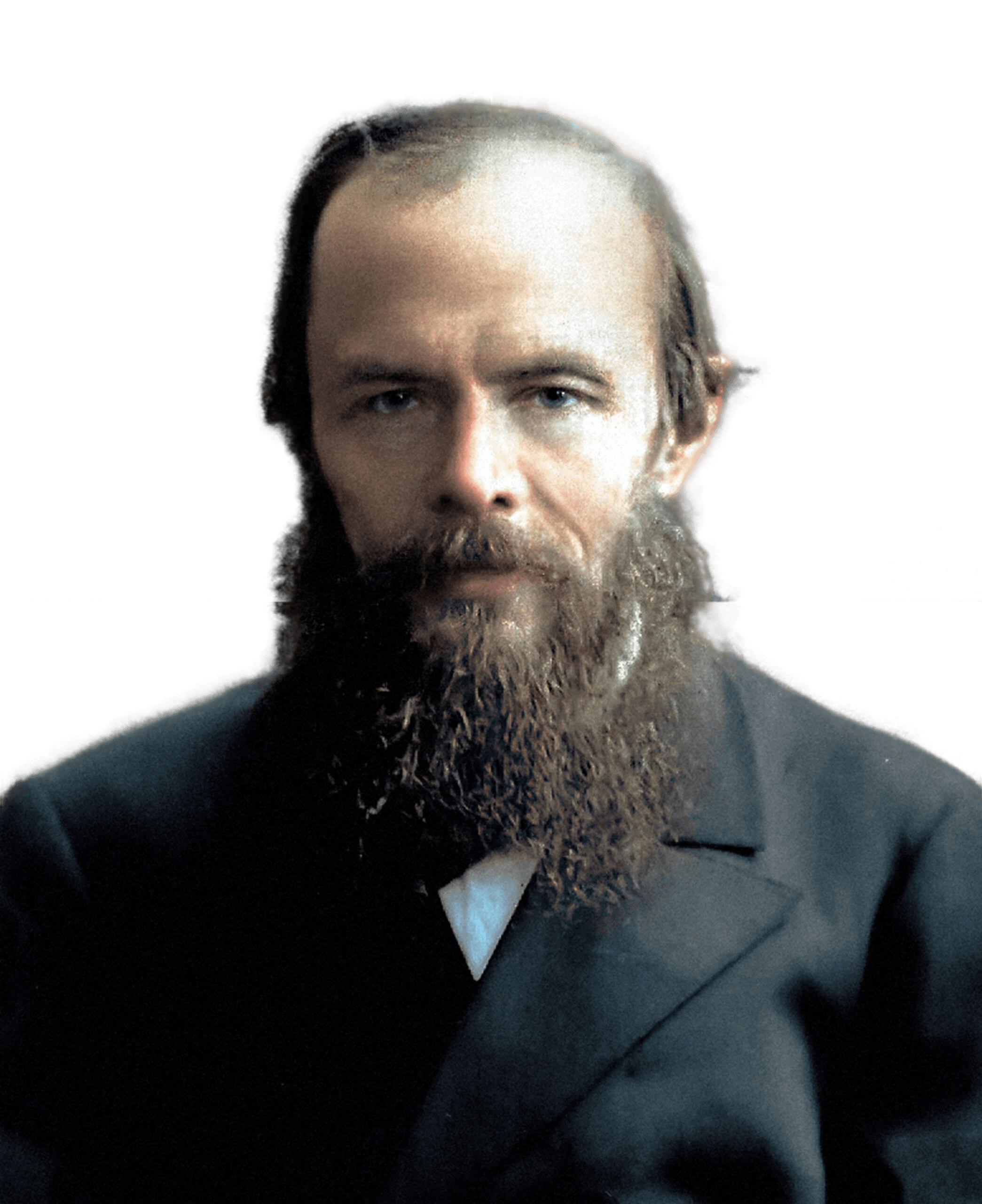

Last Love – Anna Snitkina

“Seek love and accumulate love in your hearts. Love is so omnipotent that it also regenerates us,” Dostoevsky wrote in his diary

In marriage with Anna Grigorievna Snitkina, this rebirth happened mutually, but not soon: it took a lot of effort and time to overcome Dostoevsky’s addictions, stabilize the psycho-emotional state, learn to feel and understand each other.We must pay tribute to the courage of Anna Grigorievna: as a young stenographer who came to the aid of a writer in distress, she was not afraid of difficulties, was not offended by outbursts of anger, but imbued with understanding and compassion. Recalling her first meeting with Fyodor Mikhailovich, she described her impressions as follows: “I saw a terribly unhappy man, murdered, tortured. He had the look of a man who had someone close to his heart die today or yesterday; a man who was struck by some terrible disaster. When I left Fyodor Mikhailovich’s, my rosy, happy mood scattered like smoke… My rainbow dreams were destroyed…”. However, sadness and depression after the first meeting did not become an obstacle to their joint work, and soon the “Player” was photographed, and the manuscript was handed over to the publisher on time. It was in October 1866, and in February 1867 Dostoevsky and Snitkina were married.

Inexperience, gullibility, impressionability, the ability to enjoy the world naively – all this in a young wife both attracted and saddened at the same time. “My character is sick, and I foresaw that she would suffer with me,” Dostoevsky wrote. A long trip abroad, indeed, became a great test for both of them: uncontrolled gambling addiction, despair from losing, pawning almost all things, lack of livelihood, loss of their first child, hard work on manuscripts – troubles rained down on their heads one after another. But the hardships brought them closer together and even hardened them against future difficulties. Anna Grigoryevna’s condescension and understanding were of the same quality as the writer’s mother’s feelings for her husband once were. And the methods of overcoming family troubles are the same: patience, understanding, pity, exhortation, effective help.

She gave him children, organized his life, straightened out his financial situation. After the writer’s death, she published a complete collection of his works, handed over Dostoevsky’s manuscripts to the museum, and created memories in which the personality of Fyodor Mikhailovich emerges in detail and with love. Anna Grigoryevna outlived her husband by 37 years.

In her memoirs she wrote: “Fyodor Mikhailovich sometimes told me: “You are the only woman who understood me!”” and compared her attitude to her spouse with a reliable wall, against which you can “lean, and she will not drop and warm”. Dostoevsky once wrote to his wife’s mother: “Anya loves me, and I have never been so happy in my life as with her. She is meek, kind, intelligent, believes in me, and has made me so attached to myself with love that it seems I would now die without her.” And Anna Grigoryevna, despite the significant age difference, considered her husband to be a real child, sweet, simple and naive, who should be taken care of: “It was these relationships on both sides that gave us both the opportunity to live all fourteen years of our married life in the happiness possible for people on earth.”