21.12.2022

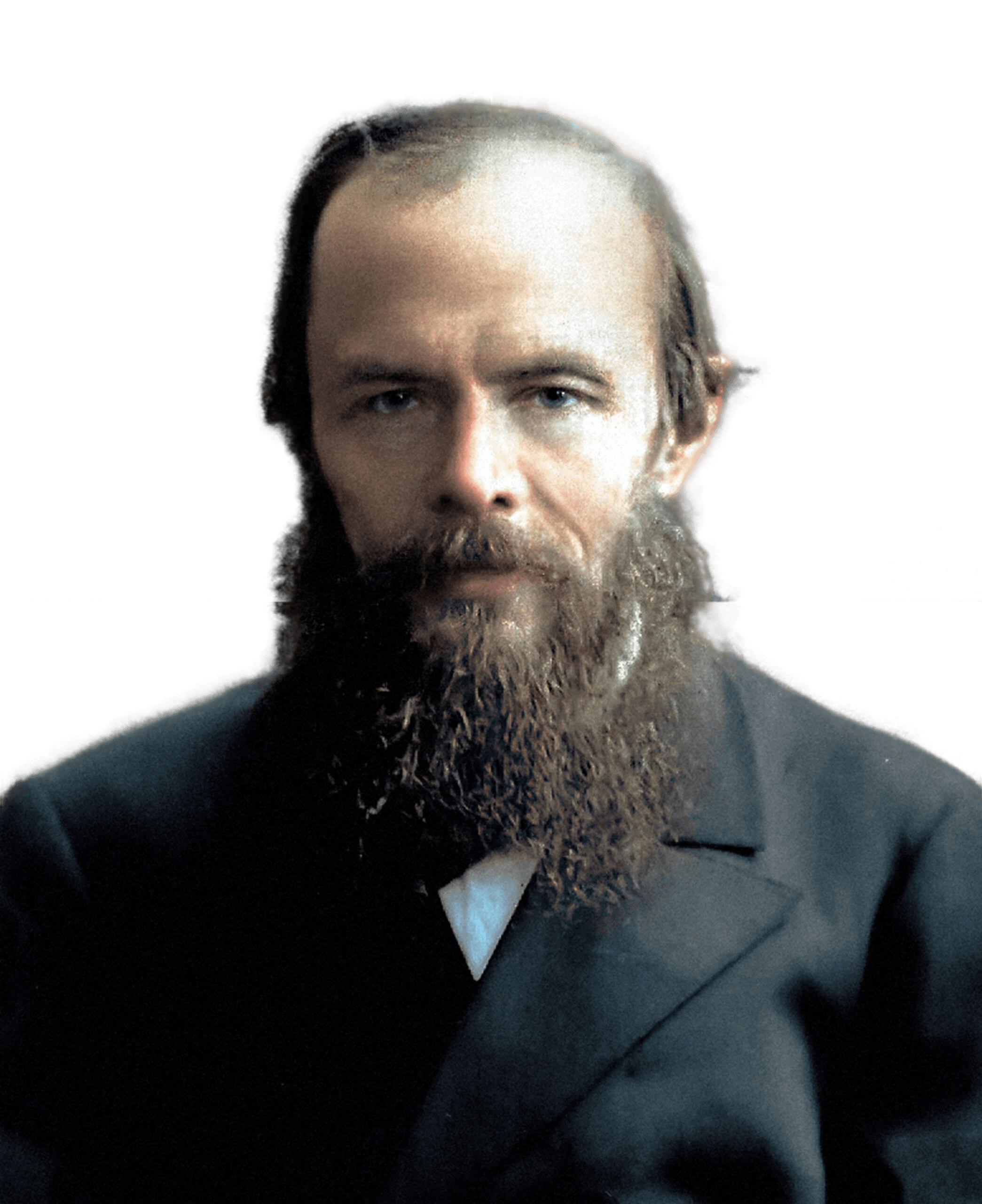

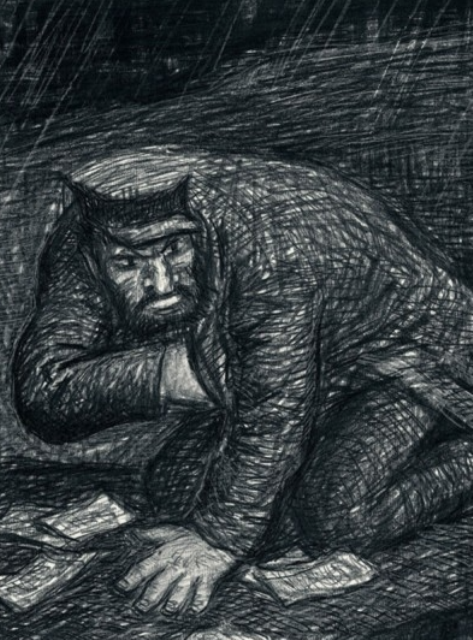

Nikolai Stavrogin, a demonic beauty, and Petrusha Verkhovensky, the son of a homeroom teacher, return to the provincial town at the same time from abroad. After their arrival, strange things begin to happen: scandals, fires and murders. Political intrigue is woven, rumours circulate, and each resident has a skeleton in his or her wardrobe. In the course of a month, the quiet town turns into a hell of a vortex, most of the characters die, go mad or flee. Dostoevsky conceives of an antinihilistic pamphlet, but writes a bleak and gripping tragedy of a world that has lost its harmony and meaning.

When was it written?

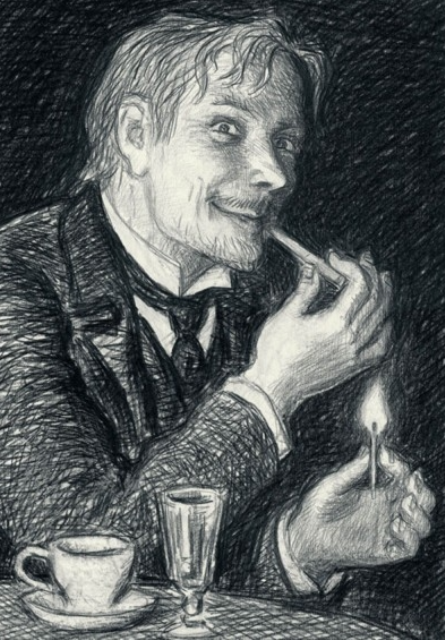

The idea began to take shape for Dostoevsky in 1869. At that time the writer was abroad, hiding from creditors, pining for his homeland and reading several Russian newspapers a day. At the same time the student movement in Russia intensifies, riots take place at Moscow University. A worried Dostoevsky invites his wife’s younger brother, Ivan Snitkin, a student at the Petrovsky Agricultural Academy in Moscow, to stay with them in Dresden. According to Anna Grigorievna Dostoevskaya’s recollections, Snitkin talks a great deal about the life and moods of the student world, including the student Ivanov. A month and a half later Ivanov is murdered by his former associates in the revolutionary organisation “Narodnaya Pravda” led by Sergei Nechaev. The student’s murder leaves a strong impression on Dostoevsky. The writer hatched the idea of writing a pamphlet against the nihilists and Westernizers, and in early 1870 he talks about this idea in letters to Apollon Maykov and Nikolai Strakhov: “What I write is a tendentious thing, I want to speak out hotter. (What the hell with the nihilists and Westerners who will scream that I am a retrograde!) To hell with them, I will speak out to the last word. Gradually the “pamphlet” grows in size, becomes more complicated and turns into a big novel, on which the writer works for almost three years.

How is it written?

The novel is a chronicle narrated by a young man, a witness and part participant in the events, Anton Lavrentievich G-v (often referred to in literary criticism as the Chronicler). The narrator tries to record in detail and objectively the events that took place in the city in September-October of one year, but as he becomes involved, his objectivity changes and individual episodes have to be speculated upon. To explain what happened, the Chronicler delves into the biographies of the characters over the previous twenty years and supplements the narrative with facts that were discovered after the denouement. The digressions and slips into the past give the impression of a great many gaps and inconsistencies, but, as the Dostoevsky researcher Ludmilla Saraskina has proved, the world of The Possessed is worked out to the minute and all it takes is for the reader to pay careful attention. The only real lacuna is between chapters eight and nine: the chapter “At Tikhon’s”, which Katkov, the publisher of the Russian Gazette, refused to publish for censorship reasons, is due to be in the middle of the novel. In modern editions the withdrawn chapter is published as an appendix, in which Nikolai Stavrogin confesses and actually explains his future suicide.

What influenced it?

The phenomenon of growing political radicalism and the political ideas, circles and corresponding discourses popular in Russia in the 1840s-60s: socialist, liberal, pseudo-genocide. An important literary source is the tradition of antinihilistic novels, which Dostoevsky transformed and developed, firstly, by presenting in his novel a complex “palette” of nihilists (at the same time as The Bes, Leskov’s novel “On Knives”, which Dostoevsky criticized in his correspondence with Maikov, was published in the Russian Vestnik: “A lot of lies, a lot of God knows what, as if it were happening on the moon”), and, secondly, by abolishing the nihilistic opposition to state power, which in “The Imp” looks in no way better than its enemies. A special case is Turgenev’s Fathers and Sons: Dostoevsky drew on them early in the novel, establishing the father-son Verkhovensky line as his predominant one, although this literary link later dissolved. The world of the provincial town in “The Possessed” reminds one of the world of Gogol’s “The Inspector” and “Dead Souls” as well as Saltykov-Shchedrin’s “History of a Town” which has just appeared (“They treased our town like a town of Glupov”, says the Chronicler about the public of the Governor’s circle. The prototype of a provincial town in The Possessed was Tver, where Dostoevsky lived after his exile in 1859 and where Saltykov-Shchedrin served as vice-governor in 1860-1862). The Tales of Belkin undoubtedly influenced the novel as well: Ivan Petrovich Belkin is the Chronicler’s closest literary relative.

How was it published?

The novel was published in The Russian Herald during 1871-1872, with a long break, which arose because of Dostoevsky’s struggle with the publisher Katkov and the editor Lyubimov over the chapter “At Tikhon’s”. In 1873 “The Imp” came out as a separate edition. “At Tikhon’s” was not published as a supplement to the novel until 1926.

How was it received? Since Dostoevsky himself regarded “The Possessed” as a tendentious book (“I should like to express some thoughts, even if my artistry is lost in it,” he wrote to Strakhov on March 24, 1870) and it was written as if it were about “The Massacre of the People”, it is not surprising that contemporaries assessed the novel mainly from the point of view of ideology. Critics, who regarded the revolutionary sentiment with apprehension, welcomed The Possessed: “Dostoevsky, with his ability to observe and analyze mostly painful phenomena of the human soul, set to trace the fatal effect of new ideas on the feeble mind and those moral expressions, what perversion of these ideas produces in the pathetic, internally untenable nature, struck by impotence and barren semi-education “- so saw the novel Vasily Avseenko, himself writing anti-nihilistic works. Democratic critics, on the other hand, accused Dostoevsky of abandoning his former convictions and of distorting the essence of the “Nechaev affair”. Pyotr Tkachev, a critic and a Narodnik, who was involved in the case (in 1881, already in exile, he wrote an article entitled “Terrorism as the Only Means of the Moral and Social Revival of Russia”), wrote about The Possessed: “The morbid notions of the freaks, who are obsessed with some indefinitely mystical points, are obviously not at all reflected in the outlook of that milieu-the milieu of the best educated youth from which they emerged.” Saltykov-Shchedrin lamented the “cheap mockery of so-called nihilism” that Dostoevsky allows himself. The conciliatory position of Vladimir Solovyov, who believed that ‘a true and impartial assessment of the novel can only be made in the distant future’, can be considered conciliatory.