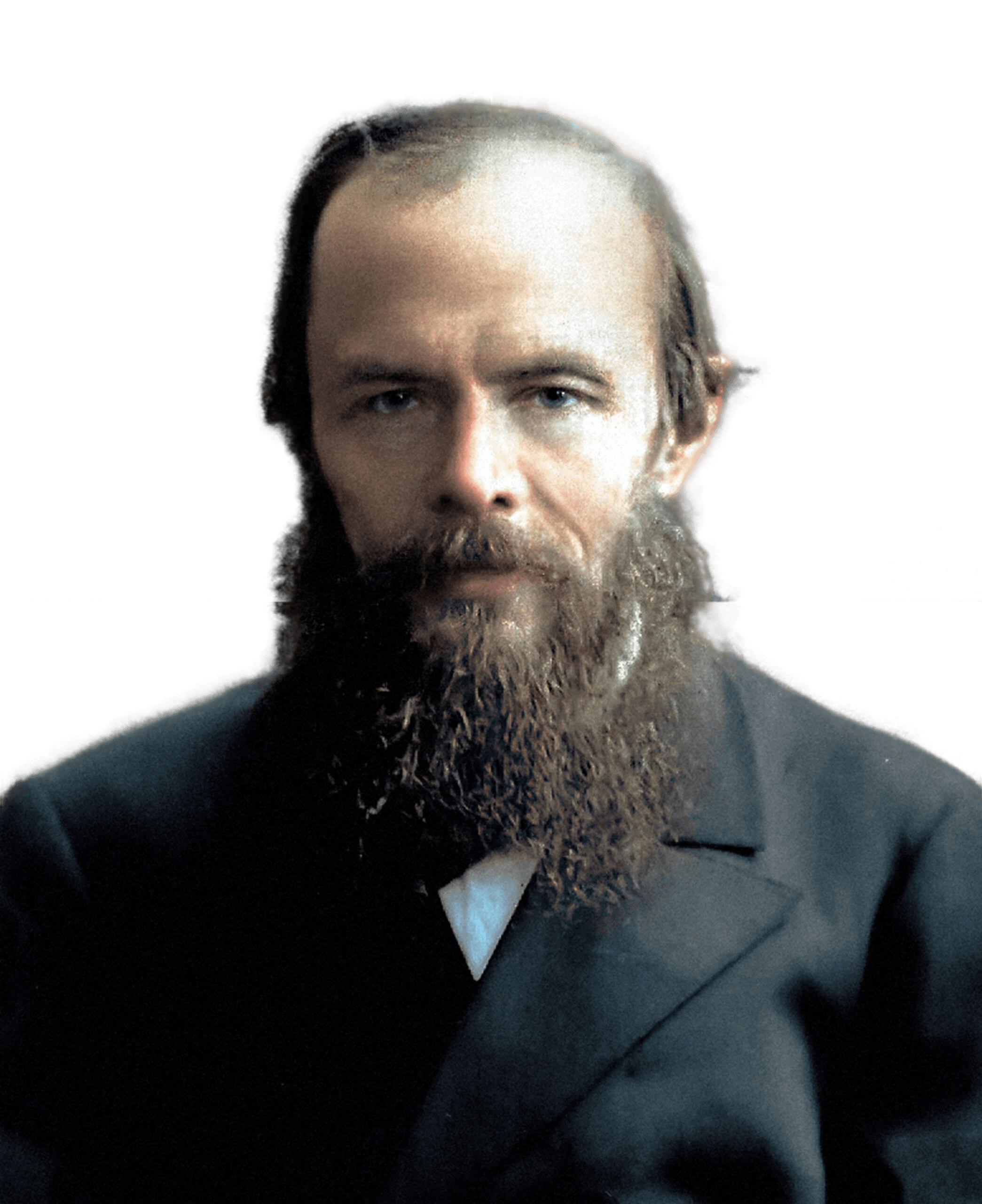

20.12.2022

Dostoevsky’s final novel and the concluding part of a five-book work in which the writer charts a way out of the ideological dead-end for modern society and polemicises the phenomena he considers the plagues of his age: atheism, materialism, utilitarian socialist morality and the decay of the family. A theosophical treatise in the guise of a detective novel about patricide, originally conceived as the first part of The Lives of the Great Sinner, through temptations coming to righteousness. Three brothers – Dmitri, Ivan and Alexei Karamazov – argue about eternal questions, resolving love and money conflicts in parallel. Is there an immortal soul? Does free will rule over man or are the laws of nature alone? Does God and the Creator exist? As Dostoevsky wrote to his editor Nikolai Lyubimov in the “Russky Vestnik” magazine: “If I succeed, I will do a good deed: I will force people to realize that a pure and ideal Christian is not an abstract matter, but an image real, possible and coming into view, and that Christianity is the only refuge of the Russian Land from all its evils.

When was it written?

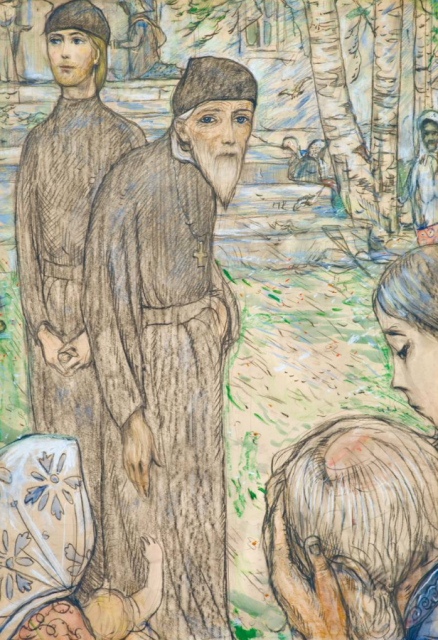

Dostoevsky contemplated the idea of his final work as early as the 1860s: at first he planned to create a cycle of two novels – “Atheism” and “The Life of the Great Sinner” – the story of the fall and resurrection of the human soul in the context of current events in Russian and world history, setting the current state of mind against the eternal problems of good and evil, faith and faithlessness. However, he managed to embody only the first part of the epic. The Brothers Karamazov” was written from April 1878 to November 1880, mostly in Staraya Russa, which is largely based on the fictional town of Skotoprigonievsk. While working on the first books of the novel, in the summer of 1878, Dostoevsky lost his three-year-old son Alexei, who died of an epileptic seizure, a disease he inherited from his father. Suffering greatly from the boy’s death, Dostoevsky, together with the philosopher Vladimir Solovyov, visited the Optina Hermitage, where he met with the elder Monk Ambrosius (Grenkov), after which “returned consoled and inspired to begin writing the novel. The writer’s wife, Anna Grigorievna, believed that the words of Ambrose were repeated in the novel by the elder Zosima to console the mother who had lost her son.

Work on the novel was delayed for various reasons, notably Dostoevsky’s illness, which forced him to leave for medical treatment; the writer died about three months after publication was completed.

How was it written?

The novel’s basic plot – a detective and melodramatic one, mingled with a few overlapping love stories and mishaps of money – is interspersed with stand-alone works. Such is, for example, the sixth book “The Russian Enoch”, containing the biography and teachings of the elder Zosima; such are “The Boys”, the “poem” of Ivan Karamazov “The Grand Inquisitor”, and “Cana of Galilee”. Here, too, are the confessions and manifestos of the heroes, not seemingly related to the plot, say the three “Confessions of a Hot Heart” by Mitya Karamazov (“In Poems”, “In Anecdotes” and, finally, “Up in Heels”). The flow of the plot is constantly interrupted by theological disputes, which are conducted by different characters and in different registers – in the cell of the elder Zosima, “Over Cognac” – in a mocking tone between the old man Karamazov and Smerdyakov, Alyosha, Mitya, Ivan and the devil.

The novel’s fantasy element is exceptionally important – the key role is played by dream scenes, Ivan’s hallucinatory conversation with the devil, and Alyosha’s visions. In general, the novel can be called realistic rather conventionally. Mikhail Bakhtin, for example, attributes the “vitally implausible and artistically unjustifiable” scenes of scandal in Dostoevsky’s novels, The Brothers Karamazov in particular (the scandal in the cell of the elder Zosima, in Katerina Ivanovna’s drawing-room, etc.) to the specific “carnival” logic of Dostoevsky’s world of fiction. As Bakhtin writes, “Carnivalization … enables the narrow stage of the private life of a particular limited epoch to be broadened into a maximally universal and pan-human mystery scene.

Another characteristic of Dostoevsky’s prose, according to Bakhtin, is its polyphony: all of the confessional statements of his characters “are imbued with an intense attitude towards the anticipated word of others about them, others’ reactions to their word about themselves. All of the protagonists in The Karamazovs are characterised by “double thoughts”: one expressed in the content of their speech and another, often unconscious of themselves, in the construction of their speech, its intonations and not always clear pauses; this inner voice materialises, for example, in Ivan’s dialogue with the devil. The narrator’s voice, as the researcher notes, adds nothing to this polyphony, becoming only one of the equal voices.

What influenced it?

A number of sources are cited in the novel directly, from the lips of the characters: such are the ancient Slavic apocrypha “The Lady of Sorrows” or Victor Hugo’s “Notre Dame de Paris” – Dostoevsky wrote a preface to the Russian translation of this novel in 1862, where he called the idea expressed in it the main idea of the art of the nineteenth century: “It is a Christian and high moral thought; its formula is the restoration of the lost man, crushed unjustly by the oppression of circumstances, the stagnation of centuries and social prejudice.” Of no less importance to Dostoevsky was ‘The Outcast’ – The Brothers Karamazov can be seen as a kind of polemic with Hugo; say, Ivan’s question about the admissibility of universal happiness at the cost of the death of a child is a response to Hugo’s opinion that the death of the young Louis XVII was justified by the high goal of the national welfare.

Mikhail Bakhtin points out the great importance which the dialogical culture of Voltaire and Diderot, which goes back to the dialogues of Socrates (in particular, in 1877 when working on The Brothers Karamazov, Dostoevsky planned to write a ‘Russian Candide’ – this plan was probably fulfilled in the novel), as well as the works of Hoffmann with his fantasy and fairytale motifs.

How was it published?

The novel was published in parts in Mikhail Katkov’s literary and political journal Russky Vestnik in 1879-1880. The December 1879 issue of the Russian Gazette, at the writer’s request, featured his letter to Katkov, in which Dostoevsky asked his readers’ forgiveness for the delay with publication: “This letter is a matter of my conscience. Let the accusations of the unfinished novel, if there are any, fall on me alone, and not on the management of the ‘Russky Vestnik’, which, if it were possible to reproach another accuser in this case, could only be guilty of extreme delicacy towards me as a writer and of constant patient indulgence towards my weakened health.

Apart from the writer’s illness, the delays were due to the fact that the plan for the novel changed considerably as the work progressed, some books almost doubled in length as planned, some chapters and books not originally foreseen were added. “Well, that’s the end of the novel! I’ve been working on it for three years, typing it up for two – a momentous time for me. I want to have a separate edition out by Christmas. People here and booksellers in Russia are asking for it, and they’re already sending money. Let me not say goodbye to you. After all, I intend to live and write for another 20 years,” Dostoevsky wrote to Nikolai Lyubimov on November 8, 1880, when he sent the epilogue of the novel to the editors of the Russian Gazette. The Brothers Karamazov was published as a separate two-volume edition in early December 1880; its success was phenomenal – half of the three-thousand-volume print run was sold out in a matter of days. Twenty years and the opportunity to write a second novel about Alyosha Karamazov, however, the author did not have: Dostoyevsky soon died.